Weekly Wrap: Relax, policymakers, it’s World Radio Day

Don’t be frustrated by the lack of a clear roadmap for radio. It’s a strength, rather than a weakness.

You may not agree with it, but the narrative for ever-greater digitisation of television is clear. Moving from analogue TV to digital terrestrial TV (DTT) freed up spectrum for mobile, contracting DTT frequencies freed up still more and brought the economic benefits of mobile broadband. Switching off DTT entirely and moving to IPTV will release yet more spectrum for mobile, with declining marginal benefits, but with savings for TV companies who won’t have to pay for transmitters.

In terms of social policy, there is the danger of leaving the elderly and poorer communities without access to TV, but this can be resolved in developed countries over the next decade by subsidies and improvements in fibre access.

What is the economic upside for the digitisation of radio? It is moderate at best. DAB allows many more stations than analogue, which enables radio companies to target niche audiences, with potential benefits for advertising revenue. But in broader terms, unlike the UHF TV bands, no “usurper” is waiting in the wings to repurpose radio’s freed-up VHF spectrum and deliver greater economic value.

What about the social policy impact? Unlike TV, radio is not on most households’ list of expensive but essential items. Cheapness is part of its USP: everyone can afford one radio, or several. The price of DAB radios will come down, but they are still three times the price of FM radios, which start at about $8. No coincidence that the countries most advanced in switching off FM radio, Norway and Switzerland, are both in the world’s top ten in terms of GDP per capita.

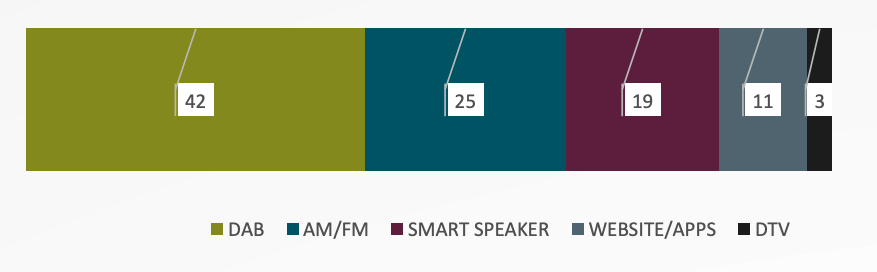

Throw technological developments into the mix, and the picture becomes more complex. Much radio listening in developed countries is now via smart speakers (i.e. internet radio) rather than over the air. In the UK, this is 19% of all radio listening, with mobile apps and websites making up 11%. These two forms of internet radio account for more listening than AM and FM (25%) but less than DAB (42%).

Are mobile apps a better bet for the future of radio than DAB? Unlike over-the-air broadcasting, they accommodate podcasts, the biggest change in radio content in decades, which are accessed by 38% of UK radio listeners. They are also likely to benefit from improvements in mobile coverage. Anecdotally, in the car, I can sometimes hear the live-ish cached service on BBC Sounds when I can’t get the DAB station.

All this makes a future radio roadmap almost impossible at a global level, very difficult at a regional level and challenging even on a national level. In Belgium, the Flemish government has dropped its 2031 DAB switchover target, concerned about potential economic damage and leaving older listeners behind.

How will radio’s trends play out? How fast will DAB listening push out FM and AM? Will internet radio leave over-the-air far behind? Will apps come to dominate? Will podcasts eclipse traditional radio formats? How will music platforms like Spotify and YouTube Music affect radio listening?

The good news is that we can wait to see how listener habits and technology usage evolve. No economic benefit is being lost by radio’s current use of the airwaves, and many social benefits are being maintained. Maybe a multiplicity of audio platforms is the best way to serve consumer, commercial and social policy interests.

World Radio Day is UNESCO’s tribute to the most widely consumed global medium, ideal for reaching remote communities and for emergency communications, and fittingly for our future-oriented discussion, this year it focuses on the role of AI in radio.

Here’s what else PolicyTracker reported on this week:

- A Saudi trial of IMT in the 7.125-7.225 GHz band offers a glimpse of what the band might be capable of in the future

- President Trump’s order to look into mid-band spectrum currently occupied by federal users for 6G has been criticised

- The UK plans to auction spectrum for supplementary downlink in the 1.4 GHz band by 2027. The upper 6 GHz band is unlikely to become available before 2030

- The Canadian regulator ISED is consulting on a new band plan for the 2500-2690 MHz band, which is used for mobile services

- UK regulator Ofcom will allow the emergency services access to 1910-1915 MHz before VMO2’s licence is officially revoked in 2029